Resiliency In Preschool

Written and researched by Daniel Lewig

Research is beginning to show that the greatest developmental need in preschool-age children is the development of resiliency.

We often think preschool is a time for abc’s and 123’s, for sorting out shapes and on the hunt for colors. The training to learn and learning how to learn are fundamental lessons in a child’s cognitive journey. The preschool years are one of the most critical (and some would argue most critical) stages of learning development. And it’s fraught with challenges that seek to stunt that development and hinder brain and cognitive learning which impact not only this stage in a child’s life but also create adverse lifelong implications.

In light of these challenges, research is beginning to show that the greatest developmental need in preschool-age children is the development of resiliency. Resiliency is a “process of and a capacity for successful adaptation despite challenging circumstances” (Bouillet, 2014, pg 437). It is a misnomer to say that resiliency is something you are born with. Over the last 20 years, studies have shown that resiliency is acquired and developed just as much as abc’s and 123’s. Harvard University and its Center on the Developing Child state, “Children are not born with resilience, which is produced through the interaction of biological systems and protective factors in the social environment.”

Some children may be born with an inclination to specific coping skills conducive to resiliency. But those same skills can be taught, developed, and encouraged. Resiliency is not just one particular skill or trait. It is a combination of internal and environmental protective factors that assist in responding to negative situations with specific skills that lead to a favorable outcome.

The Role Of Resilience In Preschool Age Children

Impact of Adverse Experiences In Early Childhood

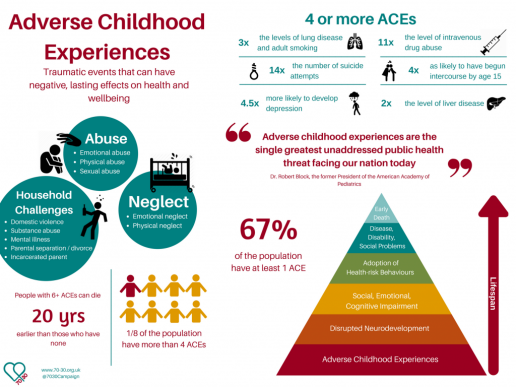

Negative situations can be especially challenging at key developmental stages, such as the formative 0-5 years. Penn State University conducted a study on the impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences on preschool age children. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) are traumatic or otherwise stressful experiences that expose children to inconsistent and unpredictable threats that harm or reduce access to safe and secure sources of social and emotional support (Sanders, 2020, pg 286). These experiences can be day-to-day adversities or a significant event such as what was just experienced during COVID. They cause disruption to the feeling of safety and security of the child. When the number of ACEs outpace positive outcomes (balance beam diagram), it leads to significant immediate and long-term health concerns.

The current environmental climate and COVID and post-COVID consequences have only increased the level of stress and potential for adverse experiences. “In recent years, concerns regarding declining resilience in children have surfaced in the academic and popular literature, alongside concerns regarding increasing stress, anxiety, and depression” (Ernst, 2021, pg 1). Immediate early childhood concerns include a disruption or fracture of attachment as well as negatively shaping brain development. ACE can disrupt the development of the physiological systems that regulate adaptive stress responding, impede the development of the prefrontal cortex, and delay the development of the self-regulatory structures that help children manage their emotions and control their attention and behavior (Sanders, 2020, pg 286). Long-term concerns include the development of mental health challenges in adolescent years and into adulthood.

Fracturing or damaging early childhood attachment is especially a concern. Child development speaks about the importance of attachment theory in a child's life. “Attachment theory posits that positive, consistent bonds with caregivers in early childhood help children predict, make sense of, and interact with their environment, especially in times of difficulty” (Sanders, 2020, pg 286). Fracturing that trust and security often leads to challenges of trust in others and developing future relationships with peers and adults, impacting school achievement (Sanders, 2020, pg 285).

Harvard University and The Center For The Developing Child have been conducting innovative research on epigenetics and early childhood brain development that are now helping us to understand cognitive development at the molecular level and how adverse childhood experiences can affect a child at the genetic level. The brain is particularly responsive to experiences and environments during early development. Experiences leave a chemical signature on genes that determines whether and how the genes are expressed. Essentially, “experiences can determine how genes are turned on and off” (Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, n.d.).

Research from the National Scientific Council on the Developing Child puts it this way:

“Over the past 50 years, extensive research has demonstrated that the healthy development of all organs, including the brain, depends on how much and when certain genes are expressed. When scientists say that genes are “expressed,” they are referring to whether they are turned on or off—essentially whether and when genes are activated to do certain tasks. Research has shown that there are many non-inherited environmental factors and experiences that have the power to chemically mark genes and control their functions. These influences created a new genetic landscape, which scientists call the epigenome. Some of these experiences lead to chemical modifications that change the expression of genes temporarily, while increasing numbers have been discovered that leave chemical signatures that result in an enduring change in gene expression” (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2010).

Too many negative experiences or when the balance beam is no longer in balance can actually change the way a child thinks. If recent research has shown us the challenge that adverse experiences can have early on, the need for teaching children how to respond to those adverse experiences must be addressed early on.

Building Resiliency in Early Childhood

Negative experiences risk the feeling and sense of safety and security of the developing child. Handling negative experiences at an early age sets the stage for life-long resiliency development. Children can be taught how to handle these negative experiences through protective factors. “Protection refers not to a universal and directly observable factor, but rather to a process or mechanism through which the detrimental developmental impacts associated with experiencing risks are mitigated to result in resilience” (Hall, 2009, pg 332). Protective factors are both internal and environmental.

The largest environmental protective factor is the parental relationship. Early childhood resilience begins with relationships. “The most important protective resource for development is a strong relationship with a competent, caring, prosocial adult” (Hall, 2009, pg 332). Extensive research and established child development theory stress the importance of forming a secure attachment between a parent and child. It is the most critical factor in helping a child establish and maintain that feeling of safety and security vital for all development. “Attachment theory posits that positive, consistent bonds with caregivers in early childhood help children predict, make sense of, and interact with their environment, especially in times of difficulty” (Sanders, 2020, pg 286). Strong adult relationships allow children to navigate risks without losing their sense of security.

Child development theories provide the roadmap for building resiliency. “If we follow the theory of (Erik) Erikson who suggested that there are three psychosocial stages, in early childhood: first, basic trust vs mistrust; second, autonomy vs shame and doubt; third, initiative vs guilt, work to develop resilience needs to build trust, autonomy and initiative in children (Bouillet, 2014, pg 438). Developing trust provides a safe environment to navigate risk and adverse experiences. Developing initiative enables and encourages children to show an interest in learning new things and making decisions for himself or herself. In resiliency, it helps children act instead of reacting and to keep going when things get difficult. Developing autonomy helps a child build confidence in themselves and their abilities. Building an environment that allows children to foster and develop these qualities that build resiliency is necessary. “If good parenting (by parents or others) and good cognitive development are sustained, human development is robust even in the face of adversity.” (Hall, 2014, pg 332)

The Role Of Faith In Resiliency

A 2011 study indicates that resilient children have four common attributes: they are socially competent, have problem-solving skills, autonomy, and a sense of purpose and future (Pratiwi, 2011, pg 142). One of the predominant ways that a sense of purpose and future is taught is through faith integration. The study from Harvard University lists faith as one of the core four factors in developing resiliency (Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, n.d.). Faith provides a foundation for hope and stability. Teaching about God and what he has done for the child further develops safe and secure relationships that help the child navigate the unknowns and adversities they face.

High Quality Preschools Impact On Resiliency Development

“A preschool institution’s climate has the power to build these strengths and overcome risk factors in the lives of children” (Bouillet, 2014, pg 438). Preschool classrooms are laboratories for children to develop social-emotional skills, such as effectively communicating feelings, managing emotional experiences and prosocially responding in frustrating situations (Bouillet, 2014, pg 435). Preschools are fundamental partners with parents and caregivers in the development of children. High quality preschools not only assist with basic child development and care for working parents, but they can provide significant assistance in building resilient children. A study from Oxford University identifies a quality preschool by 3 characteristics: environment, education, and positive adult/teacher-child relationships.

• Environment: A quality preschool environment is conducive to a child developing initiative, autonomy, and problem-solving. It is the “lab” for children to explore and the freedom to explore and interact with the world around them and the people around them. The most significant way this takes place in early childhood is through intentional play. Intentional play provides unstructured opportunities for the child to initiate interactions with his or her environment, and the peers they share the environment with, and take appropriate risks. This could also be called resilient play.

Children adapt and modify their behavior in order to best interact with the environment around them. When children master their environment, they express confidence in their abilities. Intentional and resilient play gives the opportunity for adaptability and mastery.

The best educational environment allows for self-directed exploration. Allowing students to engage in the educational process and hands-on problem solving, while wonderful benefits at any age, is especially beneficial in early childhood. This is true, regardless if the environment is indoors or outdoors. The emergence of STEM education in early childhood is about allowing children to figure out processes and develop new knowledge through the ability of trial-and-error and problem-solving. Incorporating nature into the learning environment is emerging as an effective way to build resiliency in preschool children. A study from the University of Minnesota suggests when we invest in nature-based early learning and integrate child-directed nature play into the preschool day, the returns are not only significant growth in total protective factors, but protective factors that are above typical for this age level and at a level corresponding with being considered “strengths” (Ernst, 2021, pg 11).

• Education: While building resiliency is tied to cognitive development, one of the largest components of educational focus at this age is in socio-emotional development. Children do not come with built-in emotional regulation/management. They come with built in emotions—but children need to unlock how to identify them and manage them. Many parents experience the endearing ‘Terrible two’s’ that describes a lot of this discovery process. “Resilience-focused Curriculum that focused on the promotion of SEL and early language skills, with the goal of helping children develop the emotional understanding, self-regulation, and social problem-solving skills support more positive emotional coping and social relationships as they transition into elementary school (Sanders, 2020, pg 292).

• Adult/Teacher-Child Relationships: While educators have little influence over a child’s family and larger environmental factors, it can be said that they have the power to influence certain child characteristics, such as self-concept (Nesheiwat, 2011, pg 9). Adults—teachers and parents—that promote and invest time in educational interactions with children have a larger impact. The Oxford study identified that positive, educational interactions matter more on development than other familial or SES factors (Hall, 2009, pg 343). High quality preschools that provide these three characteristics can build the foundation of resiliency skills needed as children advance in age and development and well into adulthood.

Differentiated Instruction And Resiliency

Preschool children experience a wide spectrum of development. The process of development isn’t equally linear. While there are percentiles to track “expected” development milestones and timelines, that growth happens on an individual basis, and any quality preschool needs to individualize their instruction to meet children at their developmental stage. Teaching resiliency accommodates a differentiated instruction process. Resiliency is a progression-based model, not a milestone-based model. It is about a child’s own progression and development.

Many of the factors are based on scaffolded learning, utilizing building block development of literacy and language skills and socio-emotional learning. This can be a challenge for developmentally delayed children, where some of these skills have not been developed yet to be built upon. However, an emphasis on SEL is especially beneficial for all learners, and a progression-based model lends itself to focusing on effort and not outcome. Because resiliency is a combination of protective factors, teachers can focus on the skills that do not require scaffolding, such as developing a secure and safe relationship and environment.

Resiliency: A Necessary Part Of The Preschool Development Toolbox

Preschool development goes beyond abcs and 123s. It is about providing the environment that supports a child on his/her cognitive journey. During this critical stage of child development, protective factors build resiliency to help children develop coping skills and adaptability to navigate adverse experiences and produce positive outcomes. “The active engagement to influence a situation includes the cognitive ability to perceive different options for actions to be taken, and having attitudes and values that empower a person to believe he/she can, in some way, influence their environment” (Bouillet, 2014, pg 437). Resiliency is a child having access to a wide variety of tools, having knowledge of them and their use, and selecting them to assist in experiencing good outcomes. “Even though resilience can be supported at every age, there are certain windows of opportunity where supporting the development of protective factors and harnessing the power of protective factors and systems are especially important. One of those critical windows is early childhood and heightened brain plasticity” (Ernst, 2021, pg 2). Building resilience in early childhood utilizes that critical learning window to support healthy brain development, mitigate ACE challenges, and acquire characteristics and skills that children can use to find good outcomes. This focus on whole body wellness, including the evidence-based benefit of incorporating faith integration early on in a child’s life, sets up a child for success beyond initial cognitive development to provide supportive factors that help a child navigate the challenges of development and life.

For further study on preschool and resilience, visit https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/resilience/ or consult the studies listed below.

References:

Bouillet, D., Pavin Ivanec, T., & Miljević-Riđički, R. (2014). Preschool teachers’ resilience and their readiness for building children's resilience. Health Education, 114(6), 435–450. https://doi.org/10.1108/HE-11-2013-0062

Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. (n.d.). Resilience, https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/key-concepts/resilience/.

Ernst, J., Juckett, H., & Sobel, D. (2021). Comparing the Impact of Nature, Blended, and Traditional Preschools on Children's Resilience: Some Nature May Be Better Than None. Frontiers in psychology, 12, 724340, 1-13. https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.724340/full

Hall, J., Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Sammons, P., Siraj-Blatchford, I., & Taggart, B. (2009). The role of pre-school quality in promoting resilience in the cognitive development of young children. Oxford Review of Education, 35(3), 331–352. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27784565

National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (2010). Early Experiences Can Alter Gene Expression and Affect Long-Term Development: Working Paper No. 10. http://www.developingchild.harvard.edu

Nesheiwat, K. M., & Brandwein, D. (2011). Factors related to resilience in preschool and kindergarten students. Child welfare, 90(1), 7–24. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21950172/

Pratiwi, A. (2011), “Family-based multilevel development of early childhood resilience: an effort to support the friendly city for children”, International Journal of Academic Research, Vol. 3 No. 5, pp. 142-145.

Sanders, M. T., Welsh, J. A., Bierman, K. L., & Heinrichs, B. S. (2020). Promoting resilience: A preschool intervention enhances the adolescent adjustment of children exposed to early adversity. School psychology (Washington, D.C.), 35(5), 285–298. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000406

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8447491/

Contact us to learn about how we teach evidence-based resiliency here at Bethlehem, including our nature preschool, hands-on STEM room, socio-emotional learning, and faith integration!